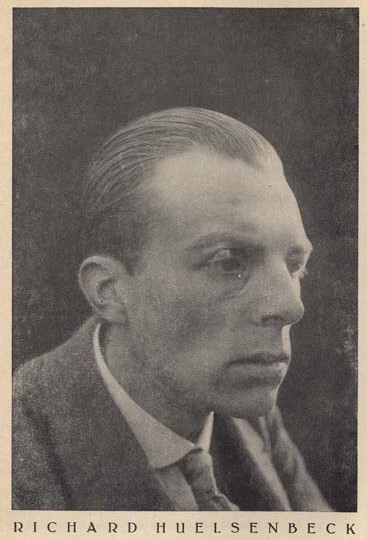

In the Fall of 2019 I delivered a paper on the Dadaist, medical doctor, and psychoanalyst Richard Huelsenbeck.

Abstract:

“Dada, Destruction, + Definition: Richard Huelsenbeck from Analysis to Synthesis”

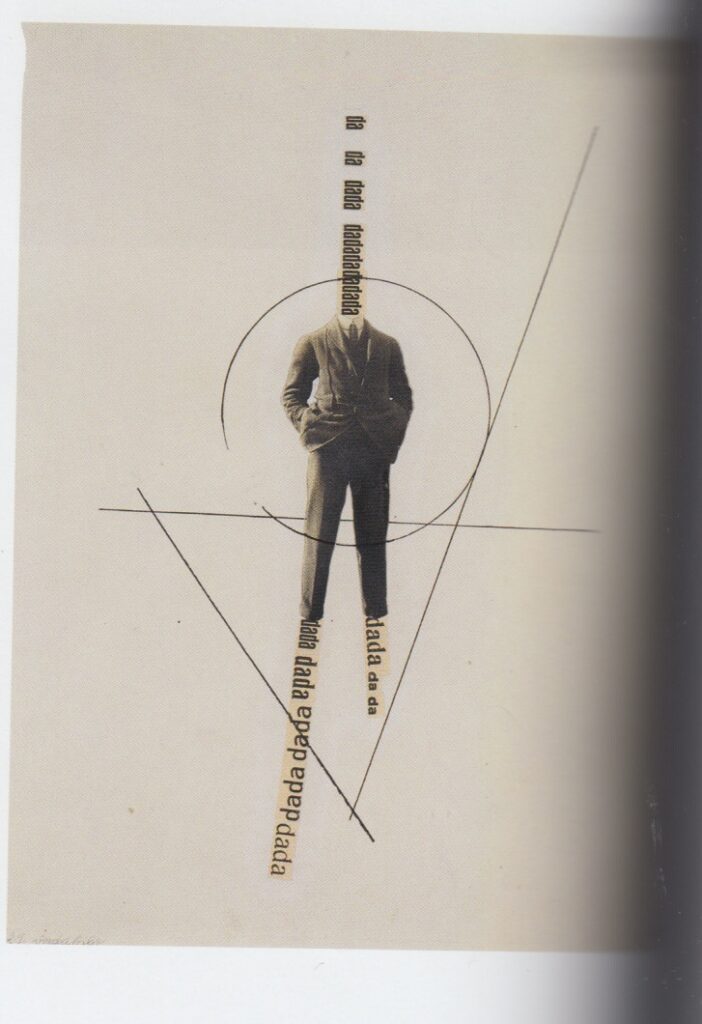

This paper explores the work of the Dadaist Ricahrd Huelsenbeck in the early and mid twentieth century. His 1949 Dada Manifesto has been widely regarded as a politically motivated re-interpretation of the nature and meaning of Dada that reflected his position as a possibly suspect foreign transplant in Cold War America. This explanation of the distance between this 1949 manifesto and the one he wrote in Germany in 1921 that called for “the international revolutionary union of all intellectual men and women on the basis of radical communism” is certainly reasonable. This paper however seeks to add additional scope to our understanding of Huelsenbeck’s Dada theorizing and the intellectual changes it represents by focusing on the structural elements of each manifesto and Huelsenbeck’s life history in the intervening period, including his work as a practicing psychoanalyst and co-founder of the Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis. What we discover by pursuing this line of inquiry are formal structural shifts that reflect Huelsenbeck’s view of Dada’s development as a system of understanding from its early analytic period of differentiation and critique to a new “mature” phase of synthesis and positive contribution. Huelsenbeck’s development as a doctor and thinker was profoundly affected by developments in existentialist philosophy (he was given the AAP’s Binswanger award for his contributions to existentialist psychiatry in 1969) and modern art. By mid-century the Surrealists were considered heirs to the initial Dada movement, existentialism had become a profoundly influential philosophical movement, and both had contributed to the understanding of the American movement of Abstract Expressionism, about which Huelsenbeck had much to say. As a German who contributed to the birth and expansion of one of the twentieth century’s most significant artistic movements Huelsenbeck’s history as a transplant in America and his further reflections on the meaning and significance of his early work and its potential for the future reveal a lot about the subsequent history of the avant-garde as German impulse was translated into American explanation. Exploring all of the aspects of this shift, beyond the strictly political, is crucial for a more complete understanding that reflects the complexity — often fraught with paradox and contradiction — of the life-history of Dada.